It is hard to believe that Jimi Hendrix died almost fifty years ago. Changes in musical taste, social values and recording industry fortunes since then have been so profound that 1970 seems many generations removed, ancient history, a black hole. It was a time of free love, of social and philosophical gurus like Abbie Hoffman and R. D. Laing, of San Francisco and hippie splendor; a time when dropping out was considered a viable, even essential career move. In this long-ago era Jimi Hendrix rose to the top of the rock world, and then departed, with breathtaking speed. Since he never grew old, he remains with us—through his music—young and wild and hypnotic.

In Crosstown Traffic by rock journalist Charles Shaar Murray, one of the many books on Hendrix and that era, we get a vivid shorthand version of Hendrix’s brief, frenzied, filmic career:

In the early morning of 21 September 1966, carrying only a suitcase and a guitar, Jimi Hendrix arrived in London, the city in which the ugly duckling of the chitlin circuit would become a gorgeous, psychedelic swan. On the morning of 18 September 1970, Jimi Hendrix died without regaining consciousness, in the city to which he had travelled with so much hope and optimism a little more than four years earlier. He was twenty-seven years old.

What happened in those four brief years has become the stuff of rock-and-roll legend. Born in Seattle in 1942, Hendrix knocked around the R&B circuit for a number of years as sideman to Ike and Tina Turner, Little Richard, the Isley Brothers and other acts before being discovered in a seedy New York club by Chas Chandler. A former drummer for The Animals and a promotional wizard, Chandler all but adopted Hendrix, taking him to London—where a black and exotic rocker was bound to get attention—and putting together the band that would make rock history as The Jimi Hendrix Experience.

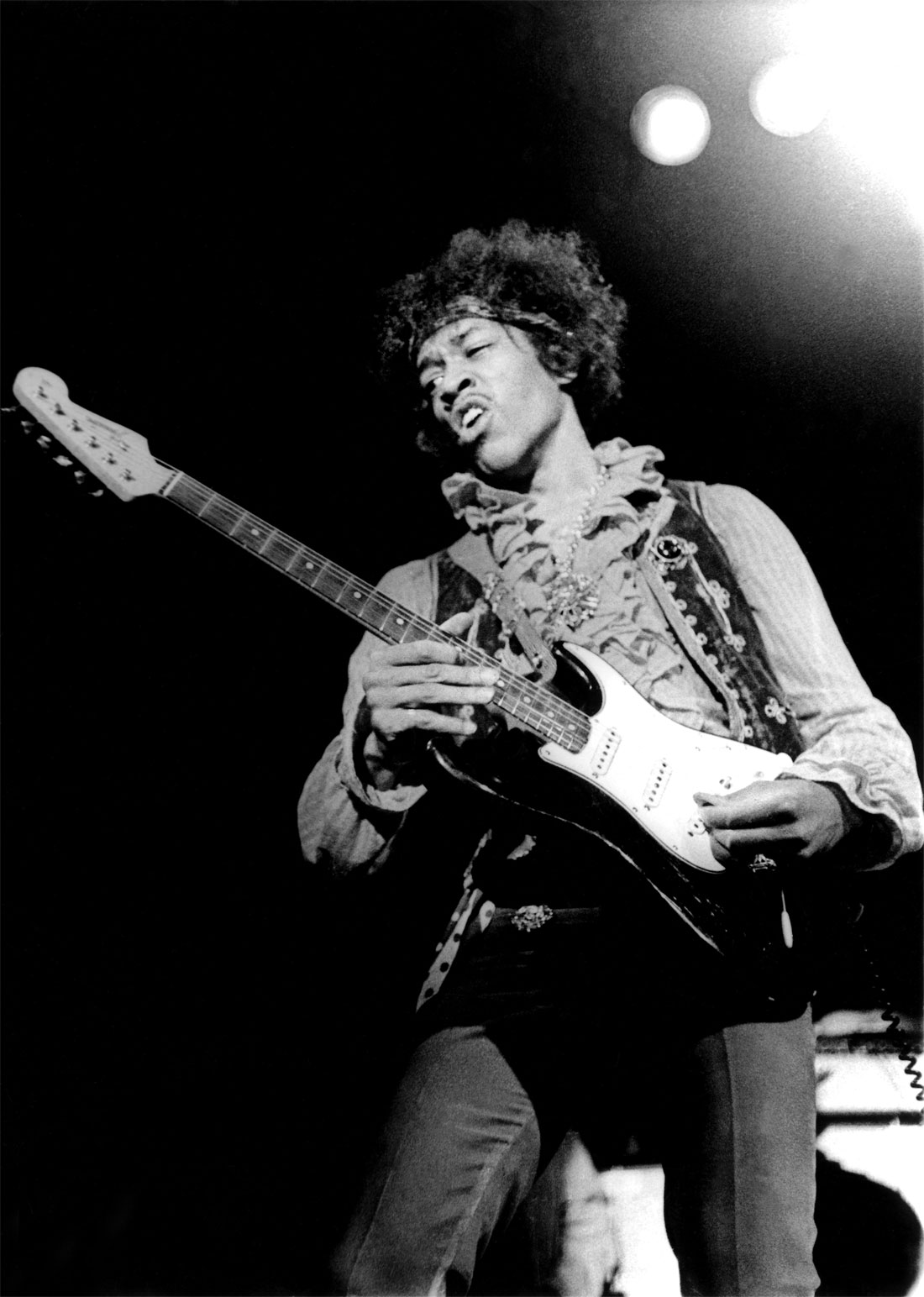

Their first single, Hey Joe, was a hit, followed by the unforgettable rock anthem Purple Haze. A punishing schedule of album-promoting tours in Europe and America, from clubs like the Bag O’Nails in London to Mile High Stadium in Denver, helped spread the band’s fame. Memorable appearances at Monterey Pop (where Hendrix ignited his guitar with lighter fluid to thundering drumbeats and applause), Woodstock and other festivals gave Hendrix the reputation of being the ultimate showstopper, a human hurricane of sound.

He could play a Stratocaster with his bare teeth. In his hands “The Star Spangled Banner” was transformed into an eerie, psychedelic blues number. While he showed total command on stage (and more sex appeal than any mortal had a right to enjoy) offstage he was shy and introspective, a bat-like creature of the night always eager to jam at after-hours clubs. His stage clothing—bright-colored scarves, love belts, Indian beaded headbands, suede fringed pouches, velvet vests, stone-studded gold necklaces—was, in fact, his everyday street clothing. Because of his flashy look, a friend recalls, Jimi “could never get a taxi in his life.”

I was reminded recently of Hendrix and his brief, meteoric career as I was looking through an old auction catalogue that included a trove of quirky items—stage clothing, jewelry, guitar picks, sketches and poetry, lyrics to songs handwritten on hotel stationery—that had been consigned for sale at Sotheby’s in 1990. The consignor, who went unnamed in the catalogue, had apparently been a business manager for Hendrix somewhere along the line, thus enabling him to assemble this little group.

As I worked at Sotheby’s at the time and was occasionally asked to write prefaces to catalogues, the head of the rock and roll memorabilia sales, Craig Inciardi, asked me to have a look at the collection and write a few words about Hendrix and these remnants of his career. Craig was very genial and enthusiastic, and he labored away in the Collectibles Department at Sotheby’s with little fanfare or recognition. Indeed, this area of the venerable old auction firm—encompassing such low-brow items as dolls, animation art, comic books, toys, automata and various memorabilia from the fields of Hollywood, sports and rock and roll—seemed to attract a sort of hobbyist clientele from which Sotheby’s was slowly moving away as it focused on the more dazzling and profitable fields of collecting like jewelry and contemporary art. And yet Craig’s brief apprenticeship at Sotheby’s served him well, as he was talent-spotted by a client who was helping to establish the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and soon became a curator there. As for his old department at Sotheby’s, it no longer exists.

And so one morning back in 1990 I found myself in a basement viewing room at Sotheby’s with the Jimi Hendrix material, all sorted and tagged and spread out before me on a large table. It looked dreary and shopworn, the sort of musty ephemera that gets thrown into boxes, stored in someone’s attic and forgotten for decades. Formally presented in a Sotheby’s sale catalogue with a preface, photographs, descriptions and notes it would be something far more compelling and desirable, a real collection. But at first glance it gave the appearance of tag sale castoffs.

And yet here was something truly electrifying, a little treasure trove of rock history, a time capsule from the Sixties. As I looked through these items before me on the table—a red velvet stage vest, a love belt fashioned from a cowbell, handwritten studio notes, a suede fringed pouch, hotel stationery from London, New York and Stuttgart with lyrics scrawled and scratched out, an Indian headband and a psychedelic scarf, doodles and drawings, a painting commissioned for a new album that went unfinished—I had to admit that, taken together, the collection stirred memories, cast a powerful spell.

Here, for example, was Hendrix’s handwritten song list for the Woodstock Festival in August 1969, along with his zonked-out impressions of that woozy, chaotic event set to poetry:

500,000 halos

outshines the mud and history.

We washed and drank in

God’s tears of Joy,

And for once, and for everyone,

The truth was not a mystery.

One item in particular jumped out at me. It was a sheet of paper that had clearly been crumpled up and then smoothed over, as if tossed aside and later retrieved. The crease marks were evident, but scribbled on that messy sheet were the words for “Purple Haze,” apparently the earliest known version of the song, written in Hendrix’s hand with alternate lyrics not included in the final recorded version. It was the Holy Grail, a druggy and wild-eyed rock anthem for the Sixties if ever one existed:

Purple haze, all in my brain

Lately things they don’t seem the same

Actin’ funny, but I don’t know why

Excuse me while I kiss the sky

I couldn’t help wondering if Hendrix himself had crumpled up this sheet, maybe tossed it into the trash and then perhaps retrieved it, smoothed it over. Or maybe someone else had retrieved it. After all, certain people make a career of preying on the trash of movie stars and other celebrities hoping to find something, anything, of value. Bob Dylan was stalked for years this way by a man named A.J. Weberman, a garbage sifter whom Rolling Stone called “the king of all Dylan nuts.” But he was an extreme case. I had to believe that the Hendrix “Purple Haze” lyrics had been salvaged and preserved by friendlier hands.

Fame is a profound judge of value in the art market. Sadly, however, Jimi Hendrix didn’t live long enough to think about his guitars, stage clothing and scraps of song lyrics and poetry as having value to future generations. But for the rock stars of today any tangible object they possess that is in any way emblematic of their fame and fortune has value far beyond reason or rationale. This is the curious but also profound alchemy of the art market.

Elton John certainly knew this back in 1988 when he decided to sell off massive quantities of shoes, tour itineraries, jewelry, costumes, dozens of his trademark eyeglasses, paintings and photographs, furnishings of all sorts, some 2,000 items in all, that had cluttered his four-story mansion in London. Packaged as the Elton John Collection, this eclectic trove was presented at Sotheby’s in London as a full-blown celebrity event, with a boxed set of catalogues, a massive public exhibition and a flood of worldwide publicity. The fans turned out in droves and the final sale result of $8,200,000 went well above expectations.

The Elton John sale in 1988 was perhaps the very first of the great rock star memorabilia events that have ensued since then, including auctions as well as museum exhibitions. If anything, the public’s appetite for the dazzle and flash of rock superstardom has only grown as a result, with an ever increasing demand for the sort of blinding, deafening spectacle one would encounter at a stadium performance by, say, The Who, The Rolling Stones or Pink Floyd. Hence was born in recent years something new: the major museum retrospective for rock’s most elite performers.

One perhaps has to give credit to the venerable Victoria & Albert Museum in London for starting this trend. For in 2013 they mounted the massive, historic, crowd-packing “David Bowie Is” exhibition, encompassing a wide array of items from the massive and well-curated David Bowie Archive of 75,000 objects. The show was mounted primarily with spectacle and performance in mind, paying tribute to one of the most creative and riveting rock stars of all time. It included some 200 items, notably musical instruments, set lists and sheet music, handwritten lyrics, diary entries from the 70s, props, and above all more than 100 dazzling costumes.

As The Art Newspaper reported, these included “the Sonia Delaunay-inspired costume designed by Bowie for his ‘absolutely extraordinary’ performance on “Saturday Night Live” in 1979; and the silver Pierrot costume created by Natasha Korniloff for the 1980’s influential “Ashes to Ashes” video.

In short, it was nothing less than the kind of full-blown retrospective major museums give to the most important living artists—only this one was for a then living rock star. Thus earphones were provided so that visitors could hear Bowie’s music while ogling the exhibits and watching footage from Bowie’s 1974 “Diamond Dogs” tour on giant screens. This brilliant and daring exhibition inspired a cascade of superlatives, and it became the most popular, well-attended event in the history of the V&A. The exhibition then traveled the world before making its final stop at the Brooklyn Museum in 2018, two years after David Bowie’s untimely death at age sixty-nine.

Taking advantage of this new phenomenon, the V&A cleverly mounted yet another rock retrospective, this one entitled Pink Floyd: Their Mortal Remains, which was held in 2017 to further rapturous acclaim. As the museum’s website informed, the exhibition presented “an audio-visual journey through 50 years of one of the world’s most iconic rock groups, and a rare and exclusive glimpse into the world of Pink Floyd with unique artefacts from every stage of their career and personal lives, brimming with eye-popping visuals, holographic representations of artwork . . .never before seen in-depth interviews with the band and those close to them.”

As if this description wasn’t enough to get the public’s full attention, the museum added that the exhibition “bristles with visual, aural and technological innovation from the moment you set foot inside.” One can only imagine where this euphoria-inducing trend will take us in the coming years, what rock superstars will be thus enshrined through museum blockbusters.

Perhaps this is a natural evolution for the field of rock and roll memorabilia, taking it well beyond its almost primitive and innocent early stages, such as the modest Jimi Hendrix sale at Sotheby’s in 1990, with its funky love belts, stage vests, guitar picks, poems and drawings that brought modest sums. Since then we have seen increasingly splashy auction events that have often featured electric guitars owned by famous musicians selling for vast amounts of money. This was the case, for example, in 1999 when Christie’s sold 100 guitars owned by Eric Clapton. The sale brought a robust $4.5 million, with the top lot, a 1956 Fender Stratocaster, achieving $450,000. It was the sort of price a vintage Ferrari might have commanded at the time!

But in the hierarchy of rock superstars no one has achieved more spectacular sale results at action than Bob Dylan, who started his career as a Greenwich Village bohemian and folk singer. In December 2013 Christie’s offered up a small group of assorted Dylan material, including newly-discovered song lyrics. But the main attraction was something much more valuable, as Christie’s announced with a flourish:

“Dylan Goes Electric: Christie’s Presents the Fender Stratocaster Guitar Played by Bob Dylan at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, One of the Most Important Concert Performances in Music History.

This guitar, estimated at $300,000-500,000, made a whopping $965,000. But then less than a year later, at Sotheby’s, Dylan magic struck again in the form of 16 pages of hand-written lyrics written in pencil on hotel stationery, with various ideas, rhymes and doodles by Dylan for his epic song of 1965 “Like a Rolling Stone.” The price: $2 million.

It is worth noting that this figure represented not only the all-time record for a popular music manuscript sold at auction but, much more impressively, the record for any American literary manuscript.

One might be shocked at the word “literary” here, for not even a manuscript by such acclaimed American novelists as Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, Sinclair Lewis or Saul Bellow has made that kind of money at auction, and probably never will. But then Bob Dylan is their equal in one important literary respect: he, too, has won the Novel Prize for literature.

Who would have thought a rock and roller would ever achieve such immortality?

—Ronald Varney

(Image: Monterey, CA – June 18, American guitarist Jimi Hendrix (1942 – 1970) plays his Fender Stratocaster guitar while performing at the Monterey International Pop Music Festival, on June 18, 1967 in Monterey, California. Photo by Ed Caraeff/Getty Images.)