Image: Four stoneware jugs displayed before a period photograph of one of the factories of Old Edgefield, South Carolina

It is often revealing to see a museum exhibition for the second time, in a different venue, and to compare the two experiences. Entirely new and even jolting aspects of the exhibition may come to light. This was the case for me with “Hear Me Now,” which presented the story, and many wondrous examples of pottery made by enslaved workers in the 19th century factories of Old Edgefield, South Carolina.

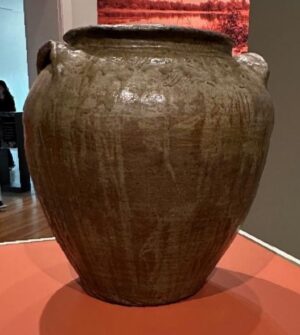

I had first seen the exhibition at the Met in early 2023. I bought the catalogue and later clipped an essay from The New York Review of Books so that I could more fully appreciate both the pottery and its backstory. It was a truly haunting show to view, featuring monumental storage jars, pitchers, decorated vases and enigmatic face vessels, nearly all of them made of alkaline-glazed stoneware created by enslaved artisans with no known names. In the cold, curatorial language of the Met, their identity was referred to simply as unrecorded, which made them sound as though they had scarcely ever existed.

But one potter did have a name. It was “Dave.”

And remarkably, not only had Dave (later identified as David Drake, 1801-1874) signed his name to thousands of pots through the decades of his forced labor in Old Edgefield but had added inscriptions—dates and locations, Christian proverbs, even musings about his family. As such, he was not only an artisan but a poet and memoirist. One of his inscriptions, for example read: “when you fill this jar with pork or beef/Scot will be there; to get a peace,—”. Another asked plaintively: “I wonder where is all my relation/Friendship to all—and, every nation.”

And while the institution of slavery made it illegal to teach slaves how to read or write, Dave clearly had learned to do both, and he wrote with poise and wisdom. As one of the catalogue essays noted, his signature and inscriptions were both a subtle form of resistance to slavery but also a means of communication. For his pots were shipped far and wide throughout the South.

I had forgotten about “Hear Me Now” until encountering it again last fall, during a weekend visit with my son to Ann Arbor. There in the University of Michigan Art Museum the exhibition was mounted anew, this time with haunting wall-sized period photographs of Old Edgefield factory interiors along with somber portraits of its enslaved workers. Many of the pots were displayed in glass vitrines, so you could examine them from all angles and savor their subtle color and elegance. The exhibition seemed more vivid and dramatic than the Met show, and perhaps because of one noteworthy distinction.

This was the language that now appeared on various exhibition placards. Where the term “unrecorded” had appeared previously in identifying the potters, in its place was the following wording:

______________(Potter Once Known)

This seemed to me a brilliant way of acknowledging that, while these potters’ names were lost to history, they were, in fact, once known. Hence the blank line presented a space on which one could imagine someone’s name being printed, an artist being recognized.

It was a subtle change, and one hardly noticeable. But it rang out, like a soft, melodic chime.

I could still hear the ringing in my ears long after we had left the museum.