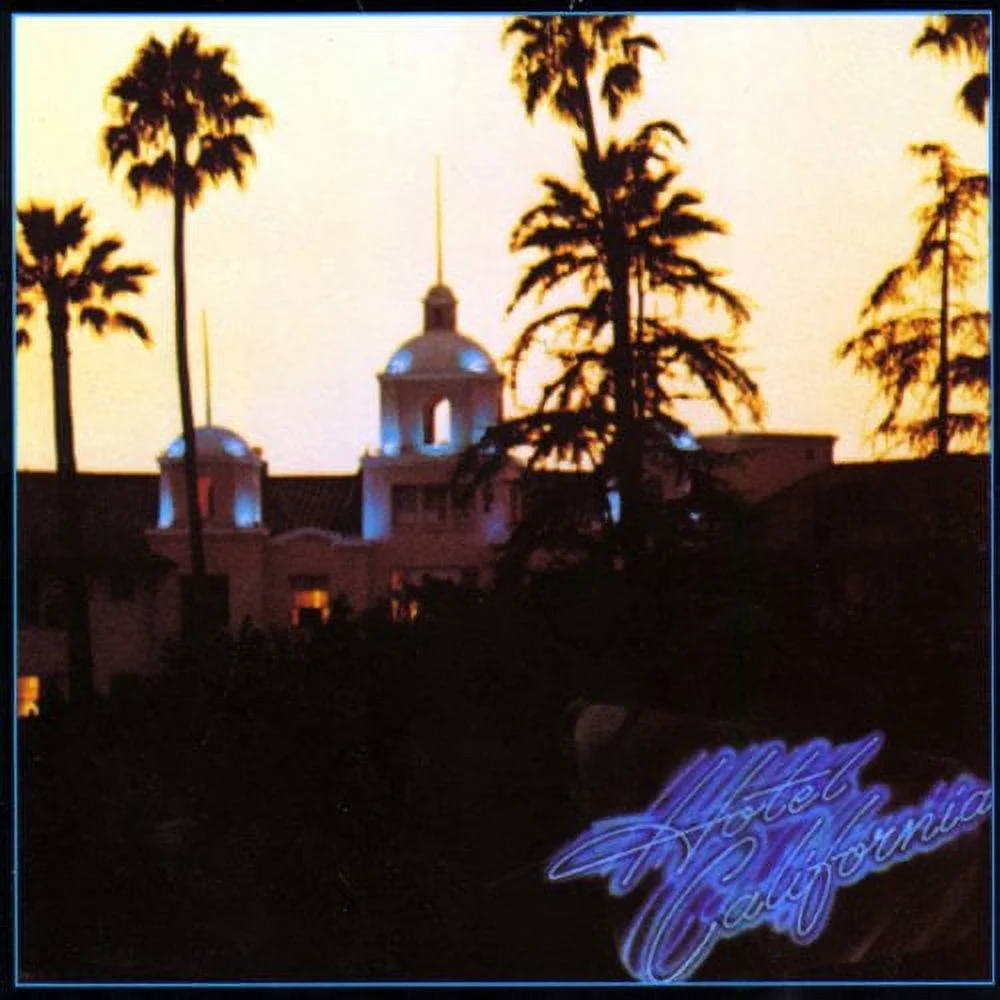

Image: Album cover, “Hotel California,” Eagles

A recent news story caught my eye, a criminal case in New York involving three art market figures accused of theft. I could scarcely believe a photograph from the court room that showed them squeezed into chairs, wearing suits and ties yet with their hands cuffed behind them like they were petty hoodlums.

The case concerned roughly 100 pages of hand-scrawled lyrics by guitarist Don Henley of the Eagles for some of the band’s most famous songs, including “Hotel California.” In the late 1970s Henley had made the pages available to a writer as research material for a biography being written about the band, a project ultimately scrapped. But the pages of lyrics mysteriously remained in the writer’s possession.

And in due course he sold them.

The buyer, prominent rare book dealer Glenn Horowitz, then resold the pages to two other individuals, which lead to various auction sale activity. Henley bought some of the pages himself, paying $8,500, but then balked when offered more.

Instead, now convinced that he was being shaken down, he sued.

I was astonished to see that one of the defendants in the case was Craig Inciardi, someone I had known from my days at Sotheby’s in the 1990s. At the time Craig ran the Rock and Roll Memorabilia Department, and eventually he was named a founding curator at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland. He seemed to have lived a charmed life in his chosen field of endeavor, at least until now.

In thinking about this case, I recalled an occasion at Sotheby’s when Craig asked me to write the introduction to a sale catalogue featuring a large trove of hand-written lyrics, clothing and jewelry once owned by Jimi Hendricks, all of it consigned by a former business manager. I sat in a basement room at Sotheby’s for a few hours looking at this fascinating material: a red velvet stage vest and a love belt fashioned from a cowbell; handwritten studio notes; a suede fringed pouch; hotel stationery from London, New York and Stuttgart with lyrics scrawled and scratched out; an Indian headband and a psychedelic scarf; doodles and drawings; a painting commissioned for a new album never recorded.

I got a chill up my spine just being alone with these strange artefacts, as Hendrix by then was a rock and roll legend, having played at Woodstock and left fans mesmerized with his every performance. But then in 1970 he died of a drug overdose in London at the age of 27.

One item jumped out at me. It was a sheet of paper that had clearly been crumpled up and then smoothed over, as if tossed aside and later retrieved. Scribbled on the messy sheet were the words for “Purple Haze,” apparently the earliest known version of the song, written in Hendrix’s hand with alternate lyrics not included in the final recorded version. It was the Holy Grail, a druggy and wild-eyed rock anthem for the Sixties if ever one existed!

At the time I couldn’t help wondering how these very personal items wound up with a business manager and not with Hendrix’s family. Perhaps in the 1990s no one really cared about such material, for it would take many years for the art market to catch up to the historic value and significance of such mundane-looking ephemera. One has only to cite as an example the sale of the Freddie Mercury Collection in 2023 at Sotheby’s in London, where a sheaf of hand-written lyrics for “Bohemian Rhapsody” brought an astounding £1,379,000.

So here was Don Henley in 2024 in a New York City courtroom, far from his home in Malibu, giving testimony against three people he claimed were complicit in the theft and sale of his own valuable and historically important hand-written lyrics. It promised to be an electrifying case.

But then it took a bizarre turn at the 11th hour.

It seems Henley and his lawyers had been withholding some 6,000 pages of documentation pertinent to the case. After first claiming attorney-client privilege, they had suddenly waived it, dumping all those pages on the defendants like confetti at a parade. The prosecution decided that the case was now tainted and asked the judge to dismiss all charges, which he did. The defendants walked free.

One felt a twinge of sympathy for Don Henley. Those lyrics of his had indeed been stolen from him. But the person responsible, that biographer back in the 1970s, had for some reason never been charged with the crime. Why?

Perhaps the answer was buried in all those 6,000 pages Henley had not wanted the court to see.

In the end, the case of the stolen lyrics from “Hotel California” was as opaque and mysterious as the lyrics themselves.